キャプティブ 2021.06.11

CA27 夏目漱石(「人間万事塞翁が馬」)Soseki Natsume ( ”fortune is unpredictable and changeable”)

目次

For those who prefer to read this column in English, the Japanese text is followed by a British English translation, so please scroll down to the bottom of the Japanese text.

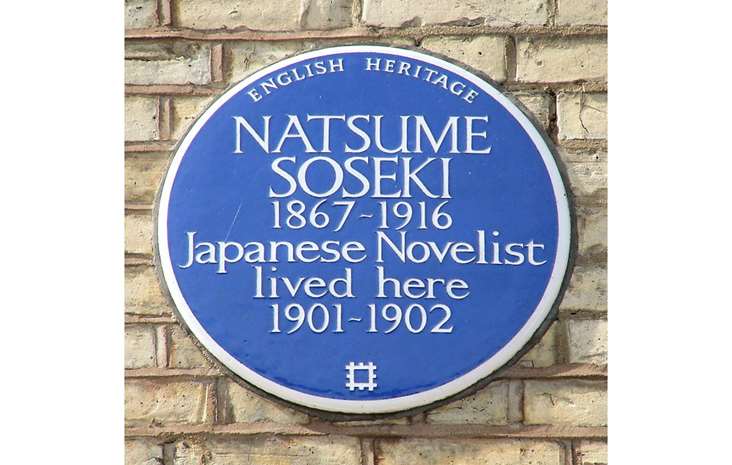

ロンドンの街を歩いていると、建物の外壁に「青い丸い銘板」が貼り付けてあるのを目にすることが多い。「ブルー・プラーク (blue plaque)」と言われるものであり、著名な人物がかつて住んだ家や歴史的な出来事があった場所に、その建物の歴史的な謂われを表わすものである。その大きさは直径19インチ(約48cm)で、陶器や樹脂によってつくられていて青地にその謂われが白文字で記されている。

現在、この「ブルー・プラーク」は、英国イングランドにある歴史的建造物を保護する目的で英国政府によって設立された組織、「イングリッシュ・ヘリテッジ」という団体が管轄、管理している。

イングリッシュ・ヘリテッジの公式ウェブサイトによるとブルー・プラークに選出される条件は、「歴史的建造物」という観点から「対象となる人物は没後20年が過ぎていること」が条件とされていて、その対象に関しては以下の記述がある。

WHO CAN GET A PLAQUE?

To be awarded an official English Heritage plaque, the proposed recipient must have died at least 20 years ago. This is to help ensure that the decision about whether or not to shortlist a candidate is made with a sufficient degree of hindsight.

However, plaques are as much about the buildings in which people lived and worked as about the subjects being commemorated – the intrinsic aim of English Heritage blue plaques is to celebrate the relationship between people and place. For this reason, we only erect a plaque if there is a surviving building closely associated with the person in question.

In the past, different criteria were sometimes used: some plaques were put up to mark the site of a house which has since been demolished, and the 20-year rule did not always apply. The plaque to Napoleon III, for example – the oldest to survive – went up when he was still alive. However, the criteria are now applied without exception.

The English Heritage scheme relies on nominations from the public, so if you think someone deserves a plaque, and fits the criteria for acceptance, please let us know.

筆者私訳

どのような人がプレートを取得できますか?

イングリッシュ・ヘリテージの公式プレートを受賞するには、受賞予定者が少なくとも20年前に亡くなっている必要があります。これは、候補者を選考するかどうかの判断を、十分な余裕の時間を持って行えるようにするためです。

しかし、プレートは、人々が生活し、働いた建物についてのものであると同時に、記念する対象についてのものでもあります- イングリッシュ・ヘリテージのブルー・プラークの本質的な目的は、人と場所の関係を祝うことです。このため、私たちは、対象となる人物に密接に関連する建物が現存する場合にのみプレートを設置します。

過去には、取り壊された家の跡を示すプレートが設置されたり、20年ルールが必ずしも適用されなかったりと、異なる基準が用いられたこともあります。例えば、現存する最古のナポレオン3世のプレートは、彼がまだ生きていた頃に設置されたものです。しかし、現在では例外なくこの基準が適用されています。

イングリッシュ・ヘリテージのスキームは、一般の方々からの推薦によっていますので、もし、プレートの設置にふさわしい人物がいて、その人が基準に合致していると思われる場合は、ぜひご連絡ください。

毎年およそ20のブルー・プラークが新規に設置されているが、これまで日本人でブルー・プラークをはただ一人夏目漱石のみであり、彼を記念するブルー・プラークが、ロンドン留学時代の最後の下宿、81 The Chase, Clapham, London, SW4 0NR, London Borough of Lambethに2002年に設置されて現在に至っている。

イングリッシュ・ヘリテッジの公式ウエブサイトには、その紹介記事が掲載されている、https://www.english-heritage.org.uk/visit/blue-plaques/natsume-soseki/

1.英国留学

「吾輩は猫である」「坊ちゃん」等、数々の名作を残し日本を代表する文豪のひとりである夏目漱石。九州の高校教師であった時代、彼は文部省派遣の国費留学生の第1号として英国に2年間留学した。ブルー・プラークが設置されている建物は、その際の下宿である。文部省派遣の国費留学生であり、「さぞかし多くの友人、知人との交流があったのでは」と思って調べてみたが実情はかなり違っていたようである。

夏目漱石は、江戸(現在の東京)の牛込から高田馬場一帯を有した大地主の夏目家に8人兄弟の末っ子として、1867年(慶応3年)誕生、「金之助」と名付けられた。父親が50歳、母親は41歳、高齢出産という、当時としては「不名誉」が広まるのを避けるため一旦、漱石は里子へ出され、1年後、夏目家に連れ戻され、その後塩原家に養子となった。しかし、塩原夫妻が離婚したため、漱石は夏目家に戻ることになった。こういった経験が、後に「人見知りで頑固」という人格形成に寄与したと言われている。

2.英語との出会い

英国への国費留学生に選抜されたのであるから「英語への造詣はかなり深い」と思ったが、どうも実情は全く逆で漱石自身が述べているが、「その頃は英語ときたら大嫌いで手に取るのも厭な様な気がした」(談話「落第」)という有様で英語は苦手だったようである。

大学予備門(旧制「第一高等学校」(現在の東京大学教養部))では腹膜炎を患い進級試験を受けられずに落第した。しかし、その後かなり学習に励んだようで、以降は殆どの教科で首席となり、なかでも英語は一番の得意科目となった。東京帝国大学(現在の東京大学)では英文学を専攻、そこでも首席で卒業した。卒業後「坊ちゃん」の舞台となる愛媛県松山市の中学校に英語教師として赴任、この地で貴族院書記官長(現在の参議院事務総長)の娘と結婚、その1年後熊本の高校へ赴任が決まり熊本での生活が始まったが、「帝国大学教授」候補として1900年(明治33年)、勤務する熊本の高校からの推薦を受け、第1号となる文部省の国費留学生に選出され、2年間の英国行きが決定した。

3.英国での苦労

現在では飛行機に乗れば12時間弱でロンドンの空の玄関、ヒースロー空港に着くことが出来るが、当時は約2ヶ月掛かる「船旅」であった。

文部省より英国留学の通達が来て3ヵ月後、1900年(明治33年)9月8日、漱石が乗った船は横浜港を出航した。上海、香港、シンガポール、マレーシア、スリランカなどに立ち寄り、スエズ運河を通過、10月19日イタリアのジェノバに到着したが、この1ヶ月間は、下痢、暑さ、また船酔いに苦しみ、食事もとれないことも多く、かなりの心労を重ねた船旅となった。ようやく、ジェノバからは船旅から解放されパリへと向かう列車へ、フランスから英国へは連絡船でドーバー海峡を渡り、ロンドン到着は10月28日、日本を発って50日間が経っていた。

そして、ようやく到着した英国、ロンドン、東京帝国大学(現在の東京大学)英文科を首席で卒業した「得意の英語が役に立つ」と思ったのも束の間、全く「漱石の英語は通じなかった」ようである。

漱石が著した「文学論(大倉書店刊、1907年(明治40年)5月初版)」、国立国会図書館デジタル コレクション(https://dl.ndl.go.jp/info:ndljp/pid/871770) に所蔵されている、この「文学論」の14ページの最後の行から15ページに掛けてその時の思いが綴られている。

倫敦(ロンドン)に住み暮らしたる二年は、もっとも不愉快の二年なり。余は英国紳士の間にあって、狼群に伍する一匹のむく犬のごとく、あわれなる生活を営みたり。

日本を代表して、「文部省派遣の第1号の国費留学生」の心情とは思えないのは筆者だけではないだろう。おそらく文部省にもそのデータが無かったためであろう、留学先の都市、大学は指定されていなかったため、漱石はケンブリッジ大学、オックスフォード大学を調べたが学費が非常に高くて断念、ロンドン大学ユニバーシティ・カレッジの聴講生となることとしたが、「文学論」に記されたとおり、ロンドンでの2年間は非常に辛い時期となったようである。

孤独と焦燥の2年間、漱石の短編集「永日小品」(えいじつしょうひん)の「暖かい事」には、以下のようにその時の心情が記されている。

道を行くものは皆追い越して行く。女でさえ、おくれていない。腰の後部でスカートを軽くつまんで、踵(かかと)の高い靴が曲がるかと思うくらい烈(はげ)しく敷石を鳴らして急いで行く。よく見ると、どの顔もどの顔もせっぱつまっている。

(中略)自分はのそのそと歩きながら、何となくこの都に居づらい感じがした。

国を背負い、国費留学生の栄えある第1号として英国に来たのに、その英国の生活になじめず疎外感を味わう日々がこの一文に凝縮されている。疎外感を味わいながら買い集めた本を読みあさり文学研究に没頭する日々が続くが、「異国人」の彼には英国文学の本質を理解することは難しかった。結局、「西洋文学者の真似事をしてみても意味が無い」と、漱石は文部省への報告書を「書くことは無い」と白紙で提出することになり、ストレスや孤独感からの疑心暗鬼から精神的に非常に抑圧された状態になっていった。この状態を見聞きした関係者からは、「漱石、発狂」との連絡が日本に届き、結果文部省は帰国命令を彼に下し、1902年(明治35年)12月5日、漱石は帰国の途に着くことになったのである。

4.帰国後

帰国後、漱石は、東京帝国大学と第一高校で英語講師となったが、精神的に追い詰められた状態は変わることはなかった。そんな漱石に手を差し伸べたのが、俳人の高浜虚子であった。彼は、漱石に自分の主宰する俳誌「ホトトギス」へ小説を投稿することを提案、1905年漱石の第1作「吾輩は猫である」が掲載された。ここから「漱石の華が開くこと」になったのである。以降、漱石は講師として教壇に立ちながらも執筆を続け、「坊ちゃん」、「草枕」のほか、英国生活からの「倫敦塔」等、多くの名作を執筆していった。

「小説家」として生きる漱石に、京都帝国大学(現在の京都大学)教授への推挙の話が届いたが、それを断り、朝日新聞社へ入社、専属作家となった。このことが、世間からは「国辱」と批判されたが、「我が道を征く」と怯むことなく、更に多くの名作を送り出していった。しかし、英国留学時からの精神的な抑圧による胃潰瘍には悩まされ続け、最後は胃潰瘍による大出血によって1916年(大正5年)12月9日に自宅で死去した、まだ49歳の若さであった。

今回のまとめ

栄えある「国費留学生第1号」として英国留学、英国では日本人唯一の「ブルー・プラーク」の対象者、数々の名作を世に送り出した明治の文豪、その後「千円札」の肖像にもなった夏目漱石。「さぞかし順風満帆の人生」と思いきや、「艱難辛苦」とも言える「英国留学」からの生活であった。帝国大学教授への推挙や文部省(現在の文部科学省)からの「文学博士号の授与」さえも辞退して、「一介の小説家」として生きた彼の人生に驚きを禁じ得ないのは筆者だけではないだろう。

漱石が渡英した頃は、日本人は遥か遠い東方に住む「異色の人種」であり、英国社会に溶け込むには大きな障壁が立ち塞がっていた。日本の英文学界でエリート街道を走ってきた漱石は、自身のプライドを大いに傷つけられ、自身の価値観も大きく覆されたのではないだろうか。

立場や時代背景は大きく異なるが、漱石の英国留学を調べていけばいくほど、筆者が大学を出て入社した外資系損害保険会社から、入社後2年目の1981年、ニューヨーク本社への「長期研修を命じられたこと」を思い出していた。偶々、「公務員試験」のため英語の勉強をしていたおかげで、入社試験の「英語の筆記試験の成績が良いので」と配属されたのが「国際・外国部門」であった。部長が米国人で、筆者以外のスタッフは全て英語が流暢に喋れた部門であった。

大学の卒業旅行に多くの学生が海外旅行をするなか、「海外に行ったこと」も無ければ、「外国人と話をしたこと」も無く、「英語が全く喋れない」筆者にとっては、会社のなかでは「誰しもが羨むニューヨーク本社研修」であったが、塗炭の苦しみを予期させた。当たり前のことであるが「出張先のニューヨークの本社には日本語を話す日本人は誰もおらず、米国人と英語で会話する以外には生活する手段が無かったから」であった。

東京とニューヨーク間を結ぶ直行便はまだ存在せず、給油のためアラスカのアンカレッジ経由の便しか無い時代であった。しかも、出発当日、飛行機が機材トラブルのため遅れ、ニューヨーク、JFK空港に着いたのは朝方3時であった。のっけから「実務英語」の出番であった。

ニューヨークを訪れた方ならご存じだと思うが、現在でもニューヨークのタクシーの運転手の多くは「移民」、しかもかなり「訛りの強い英語」の持ち主が多い。更には、ニューヨークの治安が悪かった1980年代の初頭である、その上「夜中」、「働いているタクシーの運転手」は「推して知るべし」の時代であった。

「スーツケース」の半分は「英語の辞書と英会話の教材」、後年、財閥系生保の損保子会社の経営コンサルタントを委任され、14年間に渡って、英国ロンドンに同社スタッフを研修に連れて行く度に、彼らに伝えたことであったが、帰国子女でもなく、更には英語がろくに話せない当時の筆者の「サバイバルへの覚悟が相当なものであったこと」はご想像いただけるであろう。案の定、漱石と同様、現場の英語には、学習英語は全く歯が立たなかった。しかし、その中で「救い」となったのは「ニューヨークの本社で友人ができたこと」であった。

「彼とコミュニケーションを取りたい」という「目標」ができたのである。数ヶ月間のニューヨーク研修を終え日本に戻ってきても仕事でも、そしてお互い仕事が変わっても、40年経った今でも、頻繁に遣り取りしている。そういう「目標」が出来たからこそ、「不得意だったモノ」が、いまでは本コラムの記事を拙い訳ながらも全て英語に翻訳できるようになっている。

「人間万事塞翁が馬」の喩えどおり、現状をどう捉えてどう対応していくかに尽きるのではないだろうか。この最初のニューヨーク研修からまもなく40年が経過するが、米国英語を「卒業」、ロンドン出張つまり英国英語が始まった1997年から本棚には「イギリス英語」の本がずらりと並ぶようになった。「ニューヨークに8年駐在したスタッフ」をロンドンに連れて行ったレストランでの昼食時、その彼が筆者のほうを見て「何かを訴えている」のが解った、「さっぱり解りません」とジェスチャーで言ってきたのである。英語は「全く不自由が無い」と思った彼でも、円卓を囲み次から次へと遠慮会釈無しに繰り出される「『機関銃のような英国英語』は全く解らない」ということであった。

来たるべき「コロナ禍後の英国出張の再開」を睨んで、筆者は、今でもテレビは2カ国語放送のあるものは英語音声、毎日1時間BBCニュース、映画は全て英語音声、日本語字幕、未だに「英語の勉強の毎日」である。

漱石の「倫敦消息」には次の言葉がある。

妄(みだり)に過去に執着するなかれ、いたずらに将来に望を属するなかれ、満身の力をこめて現在に働けというのが乃公(だいこう)の主義なのである。

これを個人の次元ではなく企業の次元で捉えた言葉が「リスクマネジメント」である。「満身の力をこめて現在に働く」ためには、「現在の姿」を具に識る必要がある。企業自身の強み・弱み、競合関係、事業環境等、「具に識るべき対象」は多岐にわたる。それらを一つずつ「識った」上でその対応策を案出する。そのためには筆者が最初のニューヨーク研修で「友人を得た」ような、「明確な目標が必須」ではないだろうか。

「ベクトルが明確になり、達成の可能性がより高くなるから」である。グローバル・リンクがキャプティブの設立を視野にした本格的なリスクマネジメントの遂行を提言している理由がここにあるのである。

執筆・翻訳者:羽谷 信一郎

English Translation

Captive (CA) 27- Soseki Natsume (“fortune is unpredictable and changeable”)

Walking the streets of London, it is common to see ‘blue plaques’ on the exterior walls of buildings. These are known as ‘blue plaques’ and represent the historical significance of a building where a famous person once lived or where a historical event took place. The plaques are 19 inches (48cm) in diameter and are made of ceramic or resin with a blue background and white lettering.

The Blue Plaque is now under the control of English Heritage, an organisation set up by the British Government to protect historic buildings in England.

According to the official website of the English Heritage, in order to be eligible for the Blue Plaque, “the person must have been dead for at least 20 years”.

WHO CAN GET A PLAQUE?

To be awarded an official English Heritage plaque, the proposed recipient must have died at least 20 years ago. This is to help ensure that the decision This is to help ensure that the decision about whether or not to shortlist a candidate is made with a sufficient degree of hindsight.However, plaques are as much about the buildings in which people lived and worked as about the subjects being commemorated – the intrinsic However plaques are much about the buildings in which people lived and worked as about the subjects being commemorated – the intrinsic aim of English Heritage blue plaques is to celebrate the relationship between people and place. For this reason, we only erect a plaque if there is a surviving building closely associated with the person in question.

In the past, different criteria were sometimes used: some plaques were put up to mark the site of a house which has since been demolished, and the 20-year The plaque to Napoleon III, for example – the oldest to survive – went up when he was still alive. However, the criteria are now applied without exception.

The English Heritage scheme relies on nominations from the public, so if you think someone deserves a plaque, and fits the criteria for acceptance, please let us know.

About 20 new Blue Plaques are installed each year, but only one Japanese person, Soseki Natsume, has ever had a Blue Plaque installed in his honour, at his last lodgings in London, 81 The Chase, Clapham, London, SW4 0NR, London Borough of Lambeth, where it was placed in 2002 and remains to this day.

You can find an introduction to it on the official English Heritage website: https://www.english-heritage.org.uk/visit/blue-plaques/natsume-soseki/

1. Studying in the UK

Soseki Natsume, one of Japan’s greatest writers, is the author of many famous novels including “I am a Cat” and “Botchan”. When he was a high school teacher in Kyushu, he studied in the UK for two years as the first student to receive a government scholarship from the Ministry of Education. The building in which the Blue Plaque is located was his lodgings during that time. As a government-sponsored student, I thought that he must have had many friends and acquaintances, but the reality seems to be quite different.

Soseki Natsume was born in 1867, the youngest of eight children in the Natsume family, landowners who owned the area between Ushigome and Takadanobaba in Edo (present-day Tokyo), and was named Kinnosuke. His father was 50 years old and his mother 41, and to avoid the disgrace of giving birth at such an advanced age, Soseki was sent to a foster home, where he was brought back to the Natsume family a year later and adopted by the Shiohara family. However, when the Shioharas divorced, Soseki was returned to the Natsume family. It is said that these experiences contributed to the formation of his personality, which later became “shy and stubborn”.

2. Encounter with English

Soseki was selected as a government-sponsored foreign student in England, so I thought that he would have a deep knowledge of English, but the reality was quite the opposite.

At the university’s prep school, the Dai-ichi High School (now the University of Tokyo’s College of Liberal Arts), he was struck with peritonitis and failed the examination to advance to the next level. However, he worked very hard at his studies, and from then on he was at the top of his class in most subjects, with English being his strongest subject. At Tokyo Imperial University (now the University of Tokyo), he majored in English literature and graduated at the top of his class.

After graduating, he was transferred to Matsuyama, Ehime Prefecture, where the story of “Botchan” takes place, as an English teacher, and there he married the daughter of the chief secretary of the House of Peers (now the secretary-general of the House of Councillors). A year later, he was transferred to a high school in Kumamoto and began his life in Kumamoto. In 1900, he was recommended by the high school in Kumamoto where he worked as a candidate for a professorship at the Imperial University, and was selected as the first student to receive a Japanese Government Scholarship from the Ministry of Education, which enabled him to go to England for two years.

3. Difficulties in the UK

Nowadays it takes less than 12 hours to reach Heathrow Airport, the gateway to London, by plane, but in those days it took about two months to travel by boat.

On 8 September 1900, three months after Soseki was notified by the Ministry of Education of his intention to study in the UK, the ship on which he was travelling left the port of Yokohama. The ship arrived in Genoa, Italy, on 19 October, after passing through the Suez Canal and stopping at Shanghai, Hong Kong, Singapore, Malaysia and Sri Lanka. During the month-long journey, Soseki suffered from diarrhoea, heat and seasickness, and was often unable to eat. Finally, from Genoa, he was released from the sea journey and took the train to Paris, and from France to England he crossed the Dover Strait by liaison ship, arriving in London on 28 October, 50 days after leaving Japan.

Soseki graduated from Tokyo Imperial University (now the University of Tokyo) with a first-class degree in English literature, and while he thought that his good English would come in handy, it seems that his English was not understood at all.

Soseki’s “Bungaku-ron” (The Theory of Literature), first published in May 1907 by Okura Shoten, is held in the Digital Collection of the National Diet Library (https://dl.ndl.go.jp/info:ndljp/pid/871770). From the last line of page 14 to page 15 of this “Essay on Literature”, he describes his thoughts at that time.

The two years I have lived in London have been the most unpleasant two years of my life. I lived among English gentlemen like a helpless dog in a pack of wolves.

I am sure that I am not the only one who cannot believe that this is the sentiment of “the first Japanese Government Scholarship student sent by the Ministry of Education”, representing Japan. Soseki looked at Cambridge and Oxford, but the fees were so high that he decided to become an auditing student at University College, London. The two years in London proved to be a very difficult time for him, as he wrote in his “Literary Essays”.

In “Warm Things”, a short story in Soseki’s “Eijitsu Shohin”, he describes his feelings during these two years of loneliness and frustration as follows

Everyone on the road was overtaking me. Even the women are not far behind. She pinched her skirt lightly at the back of her waist and hurried along, clacking her paving stones so hard that I thought her high-heeled shoes would bend. If you look closely, you will see that every face is urgent.

(omission) As I walked along, I felt that I could not stay in this city.

This sentence sums up the feeling of alienation he experienced every day after arriving in the UK as the first of a prestigious group of government-sponsored students, carrying the nation’s weight, but unable to adjust to life in the UK. He spent many days reading books and researching literature, but as a “foreigner” it was difficult for him to understand the essence of British literature. As a result, Soseki was forced to submit a blank report to the Ministry of Education, saying that he had nothing to write about and that there was no point in trying to imitate Western writers. The Ministry of Education ordered Soseki to return to Japan, and he did so on 5 December 1902.

4. After his return

After returning to Japan, Soseki worked as an English teacher at Tokyo Imperial University and Dai-ichi High School, but he remained in a state of mental depression. The haiku poet, Kyoshi Takahama, reached out to Soseki. He suggested that Soseki submit a novel to his haiku magazine, “Hototogisu”, and in 1905 Soseki’s first novel, “I am a Cat”, was published.

This was the beginning of Soseki’s flowering. From then on, Soseki continued to write while teaching, and wrote many masterpieces, including “Botchan”, “Kusamakura” and “London-Tower” from his life in England.

Soseki was offered a position as a professor at Kyoto Imperial University (now Kyoto University), but he turned it down and joined the Asahi Shimbun, where he became an exclusive writer. This was criticised by the public as a “national disgrace”, but Soseki was undaunted and went on to produce many more masterpieces. However, he suffered from gastric ulcers caused by the mental oppression of studying in England, and finally died of severe bleeding caused by a gastric ulcer at his home on 9 December 1916, at the age of only 49.

Summary of this issue

Soseki Natsume was the first Japanese student to be awarded a Japanese Government Scholarship to study in England, the only Japanese to be awarded the Blue Plaque, and a great writer of the Meiji era who produced many masterpieces. Soseki’s life has been a smooth sailing life as one might expect, but it was a life of hardship, starting with his study in England. Soseki turned down an invitation to become a professor at Imperial University and even a doctorate in literature from the Ministry of Education (now the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology), and lived his life as a novelist.

When Soseki arrived in England, the Japanese were a “different race” living far to the east, and faced huge barriers to their integration into British society. Soseki, who had been a member of the elite of Japanese English literature, must have felt his pride and his values challenged.

Although the circumstances and the historical background were very different, the more I researched Soseki’s study in the UK, the more I remembered that in 1981, two years after I joined a foreign non-life insurance company, I was ordered to go to New York for a “Long-term training course”. By chance, I had been studying English for the Civil Service Examination and was assigned to the International and Foreign Affairs Division because of my good score in the written English examination. The manager of the department was an American and all the staff spoke English fluently except for me.

While many students went abroad on their graduation trips, I had never been abroad, had never spoken to a foreigner, and could not speak any English. As a matter of course, there was no one who spoke Japanese at the head office in New York, and I had no other way to live except to talk with Americans in English.

There were no direct flights between Tokyo and New York, and the only way to get there was via Anchorage, Alaska, for refueling. Moreover, on the day of my departure, my flight was delayed due to aircraft trouble, and I arrived at JFK Airport in New York at three in the morning. From the very beginning, it was the turn of “Practical English”.

If you have been to New York, you may know that most of the taxi drivers in New York are still immigrants, and many of them speak English with a strong accent. Furthermore, it was the early 1980’s when New York was not safe, it was the middle of the night, and the taxi drivers working in the taxis were “you guessed it”.

Half of my suitcase was filled with English dictionaries and English conversation materials, which I would tell the staff every time I took them to London for training over the next 14 years as a management consultant for a non-life insurance subsidiary of a conglomerate. I was not a returnee and could not speak English very well, so you can imagine that I was quite prepared for survival.As expected, like Soseki, learned English was no match for field English. What saved me, however, was the fact that I had made a friend at the head office in New York.

I had a goal to communicate with him. After months in New York, I came back to Japan and we still communicate with each other frequently at work, even after 40 years. Because of this “goal”, I am now able to translate all the articles in this column into English, even though they are poorly translated.

As the saying goes, “fortune is unpredictable and changeable”, it is all about how you perceive the current situation and how you respond to it. It is now almost 40 years since my first trip to New York, and since 1997, when I “graduated” from American English and began my business trip to London, my bookshelves have been lined with books on “British English”. When I took a staff member who had been in New York for 8 years to London for lunch, I noticed that he looked at me and said “I don’t understand at all” with a gesture. Even though he thought his English was “perfectly good”, he could not understand “British English like a machine gun”, which was spoken one after another without any reservation around the round table.

In anticipation of the coming “resumption of business trips to the UK after the Corona disaster”, I still use English sound for bilingual TV broadcasts, BBC news for one hour every day, English sound for all movies with Japanese subtitles, and I am still “studying English every day”.

In Soseki’s “London Shosoku” (Notes from London), there are these words.

It is the principle of Daiko (ie: (pompous) me) to work in the present with all one’s strength, not to cling to the past or to hope for the future unnecessarily.

The term “risk management” is used to describe this in the context of a company rather than an individual. In order to “work in the present with all one’s strength”, it is necessary to know “what the present is”. There is a wide range of subjects that need to be considered, including the company’s own strengths and weaknesses, competitive relationships and the business environment. The first step is to find out what you need to do. In order to do this, it is essential to have a clear goal, as I did when I first studied in New York. The more clear the vector, the more likely it is to be achieved. This is why Global Link recommends the establishment of captives and the implementation of a full-scale risk management program.

Author/translator: Shinichiro Hatani